After years of fits and starts - and not inconsiderable controversies - it appears that an initiative born in 2014 to quell gang violence in Chattanooga may at last be coming of age.

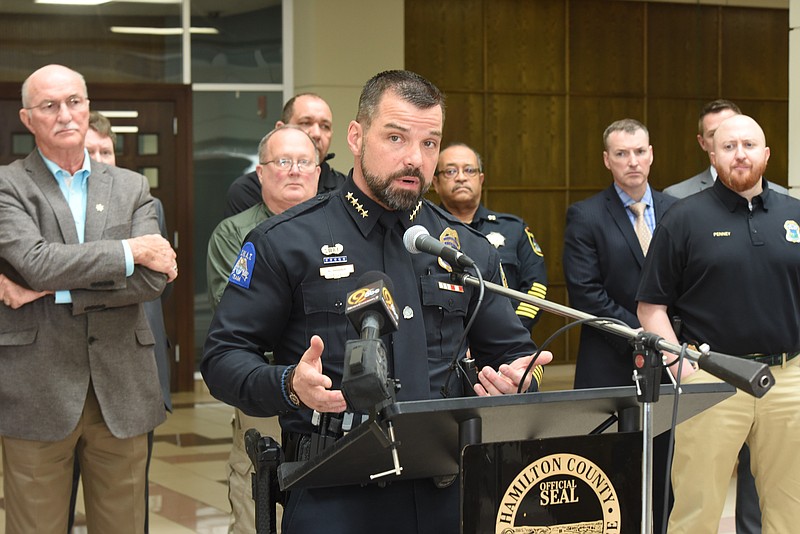

Cooperation, it seems, goes a long way, and now - thanks to the combined work of Chattanooga Police and the Hamilton County District Attorney's office - the Hamilton County grand jury on Wednesday indicted 54 Athens Park Bloods gang members on charges ranging from aggravated kidnapping to first-degree murder. Seven of the 54 are charged in five homicides.

The indictment marks the first time a street gang in Hamilton County has been prosecuted as a criminal enterprise under Tennessee's Racketeer Influenced and Corrupt Organization Act, known as RICO.

But the work on gang violence actually began four years ago when the city announced its new Violence Reduction Initiative that became known as VRI. A carrot-and-stick type program, the VRI aims at gang members - especially those who shoot and shoot back. It was tailored to encourage police and prosecutors to use every legal means at their disposal to deter current and future gang violence through the use of social assistance or - if necessary - stacked cases or special statutes to obtain long jail sentences for offenders. Gang members have a choice, however. They can voluntarily leave gang life and receive a range of social services meant to help them get jobs and get their lives straight, or they can end up in jail for a long time.

These 54, authorities say, used up their chances. Nearly half of the defendants already were incarcerated on previous charges.

The new racketeering charges are the fruit of work by officers and investigators from the police department and the District Attorney's cold case unit. Authorities reviewed a string of unsolved homicides and combined their new research with cases officers had built over months and recent years.

A perfect example is the indictment connected to the death of Bianca Horton, who authorities say was murdered to prevent her from testifying at trial that she witnessed Cortez Sims, one of the men indicted, murder another woman. Police say Sims burst into a College Hill Courts apartment early in the morning on Jan. 7, 2015, and opened fire, killing Talitha Bowman and wounding two others, one of whom was Zoey Duncan, Horton's infant daughter. A little over a year later, Horton was found dead on the side of a road with multiple bullet casings on the ground beside her. Courtney High, 27, Andre Grier, 31, and Charles Shelton, 28, have all been charged with Horton's murder and could face the death penalty. The indictment has also added the RICO elements to High's charge for the slaying of Jerica Jackson and additionally charged him with murder in the death of Marquise Jackson. Both of those slayings occurred in the months after Horton's death.

Using the state RICO law, passed in 1986, prosecutors can seek extended criminal penalties for individuals operating as part of an ongoing criminal organization. Specifically, it allows leaders or associates to be tried for crimes they ordered others to do or helped them commit.

RICO's extended sentencing is a tool that both the DA and the police could agree on in the VRI, but that hasn't always been the case.

In VRI's first year and a half, there was constant friction. Police and city officials were often trading barbs with the DA, each accusing the other of dropping the ball. Some 19 months and 251 criminal cases after VRI was adopted, most of the crimes had gone unpunished. Police pointed the finger at the DA's office, noting - and numbers bore this out - that most cases were brought as misdemeanors (meaning the maximum possible jail time would automatically be less than a year), pleaded down to lesser crimes or dismissed altogether. District Attorney Neal Pinkston said the police work wasn't up to par and that he had to treat all cases the same, meaning he couldn't seek extra jail time just because a defendant was gang member and the case was brought under the VRI.

Now that authorities agree that using RICO allows these 54 gang members to be treated differently and now that the city has assigned one of its investigators to the DA's cold case unit, it appears compromise - and Chattanooga residents - have won out. Time and numbers will tell if this becomes a real turning point.

VRI was never intended to be the silver bullet to end gang violence here, and so far the impact has been uneven. At the end of 2017, gang-related shootings had declined by almost 30 percent - to 64. But that was really about even with the tally for 2014 - the year VRI began. Each of the years in between saw an extra dozen or so shootings.

Still, we have to ask ourselves what would have happened without VRI and the well over $1 million in surveillance equipment and manhours the city also employed.

Local officials like to call VRI another "tool" to combat gang violence, but the truth is it's a Band-Aid. We can't arrest our way out of gang violence, we have to educate and employ our way out.

In Chattanooga, we've allowed hundreds - thousands - of young black children to continue cycles of poverty in low-performing schools where, by third grade, scores show students cannot read well enough to keep learning. Those students eventually drop out or are expelled - doomed to be unemployable, doomed to find the rest of their schooling in Gang University. We might just as well have given these young people their guns and pulled the triggers ourselves.

Whatever it takes, we have to make VRI - and our schools - work.